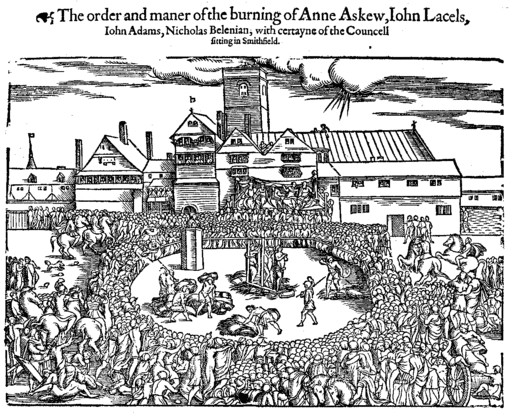

Woodcut of the burning of Anne Askew at Smithfield in 1546

Anne Askew, [married name Kyme] (c. 1521–46), the second daughter of Sir William Askew (1489–1541) and his first wife, Elizabeth Wrottesley who was probably of the Reading Wrottesleys, though some sources say Wrottesley, Staffordshire.[1] Anne Askew is thought to have received a good education, possibly from tutors at home. She was married to Thomas Kyme in 1536 as a replacement for her sister Martha who died before their wedding could take place. The couple had two children. The description of her life by John Bale, who published her writings posthumously, are accepted as reliable, despite his editorial adjustments to her works. Her enthusiastic conversion to Protestantism drew hostile attention from the local community. Protestant and Recusant propagandists present conflicting accounts; some suppose that her public confrontations prompted her husband to drive her from the family home which led her to seek legal separation, others that she left her spouse for a life of preaching and court life.[2]

Anne Askew was imprisoned twice and harassed during the two years prior to her execution. The exact order of events is unclear. She was caught up in the religious and political uncertainty of the last years of Henry VIII’s reign, as conservatives and reformers competed for a position which would give them control of government when the king died and a minor succeeded.[3] On the first detention she was cross-examined for heresy and her beliefs. Her friends interceded on her behalf and negotiated her release on bail.

On her second appearance before the Privy Council, the interrogations focussed on her connections and contacts, in addition to her beliefs. Her husband was required to attend with Anne. She denied he was her husband and he returned home. Despite threats of execution, Askew refused to recant. She was arraigned for heresy and condemned without a trial by jury. It was said that she had contacts with noblewomen at court, who sympathized with her religious persuasions. This gave the conservative faction grounds for hoping she could be induced to incriminate these women, and by implication their husbands, and so ruin the reformist cause in the eyes of the doctrinally conservative king. Councillors tried to force Askew to name other members of her sect; when she refused, they took the exceptional step of having her tortured, and even going so far as to turn the rack themselves.[4] As a woman, gently born, and a condemned person, she should have been exempt from such treatment.

Askew was questioned about whether she had received any support from members of the Privy Council, and specifically asked about women in the queen’s immediate circle who were evidently suspected of encouraging the spread of Protestantism. Her torturers were probably also motivated by the hope that she would incriminate the queen: Katherine Parr was a committed religious radical. The unlawfulness of these proceedings caused the Privy Council some anxiety, but attempts to cover them up did not succeed. On 16 July 1546, Askew was burnt at the stake in Smithfield. Propagandists on both sides produced fictionalized accounts of the execution.

John Bale’s editorial insertions, introduction, commentaries and conclusion to her works served his goal as chronicler of protestant martyrs. His edition ensured her place as a protestant saint and a Renaissance woman writer. His depiction of Askew as young, weak, and tender, if also brave and steadfast, is at odds with her own self-representation as a disputatious individual, confident of her salvation, and inspired to follow in the footsteps of Christ.[5]

Askew seems to have written down the events that led up to her condemnation at the request of religious sympathizers. She evidently hoped that her narrative would encourage others in adversity. Askew’s autobiography (without Bale’s additions) in John Foxe’s Acts and Monuments of protestant martyrology ensured its continuing popularity and her reputation.

One of the most remarkable tributes to Askew was made in 1673 by Bathsua Makin, formerly a tutor in the household of Charles I, when she called her ‘a person famous for learning and piety’ and claimed that Askew had ‘so seasoned the Queen and ladies at Court, by her precepts and example, and after sealed her profession with her book, that the seed of reformation seemed to be sowed by her hand’[6]

[1] Elaine V. Beilin, “Anne Askew,” Mary Hays, Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries (1803). Chawton House Library Series: Women’s Memoirs, ed. Gina Luria Walker, Memoirs of Women Writers Part II (Pickering & Chatto: London, 2013), vol. 5, 226-34, editorial notes, 444-45, on 444.

[2] Diane Watt, ‘Askew, Anne (c.1521–1546)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004) accessed 20 March 2014, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/798.

[3] Watt, ‘Askew, Anne (c. 15219-1546),’.

[4] Mary Hays, Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of all Ages and Countries (6 volumes) (London: R. Phillips, 1803), vol. 1, 200-8, on 206.

[5] Watt, ‘Askew, Anne (c.1521–1546)’.

[6] Watt, ‘Askew, Anne (c.1521–1546)’.

Bibliography

Ballard, George. Memoirs of several ladies of Great Britain, who have been celebrated for their writings or skill in the learned languages arts and sciences. Oxford: printed by W. Jackson, 1752.

Beilin, Elaine V. “Anne Askew.” Mary Hays, Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women, of All Ages and Countries (1803). Chawton House Library Series: Women’s Memoirs, ed. Gina Luria Walker, Memoirs of Women Writers Part II (Pickering & Chatto: London, 2013), vol. 5, 226-34, editorial notes, 444-45.

Biographium fæmineum.The female worthies: or, memoirs of the most illustrious ladies, of all ages and nations, … Collected from history, and the most approved biographers, (2 volumes). London : printed for S. Crowder, and J. Payne; J. Wilkie, and W. Nicoll; and J. Wren, 1766.

Foxe, John. Book of martyrs: the acts and monuments of the Church. London: Printed for the Company of Stationers, 1684.

Gibbons, Thomas. Memoirs of eminently pious women, who were ornaments to their sex, blessings to their families, and edifying examples to the Church and the world (2 volumes). London : printed for J. Buckland, 1777.

Hays, Mary, “Anne Askew.” Female Biography; or, Memoirs of Illustrious and Celebrated Women of all Ages and Countries (6 volumes) London: R. Phillips, 1803, vol. 1, 200-8.

Hume, David. The history of England, from the invasion of Julius Cæsar to the revolution in 1688. London: printed for J. Parsons, 1793.

Makin, Bathsua. ‘An essay to revive the ancient education of gentlewomen’, The female spectator: English women writers before 1800, ed. M. R. Mahl and H. Koon (1977).

Watt, Diane. ‘Askew, Anne (c.1521–1546).’ Oxford Dictionary of National Biography Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 20 March 2014, http://www.oxforddnb.com/view/article/798.

Resources:

Brooklyn Museum

Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art: The Dinner Party: Heritage Floor: Anne Askew

http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/heritage_floor/anne_askew.php

Page citation:

Penelope Whitworth. “Anne Askew.” Project Continua (June 17, 2013): Ver. 1, [date accessed], http://www.projectcontinua.org/anne-askew/

Tags: End of Renaissance, Europe, Reformation, Religious Thinkers