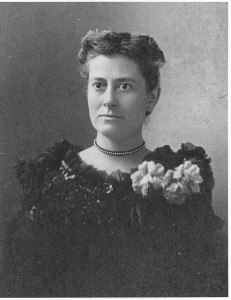

- Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (1857-1911), circa 1890s. Courtesy Curator of Astronomical Photographs at Harvard College Observatory

- ‘Pickering’s Harem’ standing in front of Building C at the Harvard College Observatory, 13 May 1913.

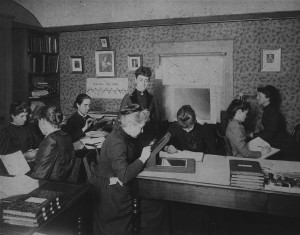

- Harvard computers, circa 1890. Seated, third from left, with magnifying glass: Antonia Maury; standing, at center: Williamina Fleming

By Lindsay Smith

Williamina Paton (Stevens) Fleming (known often as “Mina”) (1857-1911) She was born on May 15, 1857, in Dundee, Scotland. Her father, Robert Stevens, carved and gilded picture frames and furniture; he died when his daughter was seven.[1] Around the age of fourteen Fleming became a pupil-teacher, a common practice for bright students in Scotland.[2] In 1877 she married James Fleming and they moved to America a year later, settling in Boston. After discovering she was pregnant, Fleming’s husband abandoned her, forcing her to find work so she could survive and care for their child on her own.[3] Edward Charles Pickering, an astronomer at the Harvard College Observatory in Cambridge, Massachusetts, hired her to be his housemaid, but was so impressed by her intelligence that in 1879 he also hired her to conduct part-time administrative work at the observatory.[4]

Pickering’s staff at Harvard was collecting and analyzing glass plate photographs of the sky because these photos captured more detail than could be seen with an observer’s naked eye through a telescope.[5] As the story goes, in 1881 Pickering became frustrated with the men he had hired to work on the photograph project and reportedly yelled, “My Scottish maid could do better!” He then taught Fleming how to analyze stellar spectra with a magnifying glass, and hired her as the first of the famous Harvard Computers, women who studied the stars through the university’s glass plate photographs.[6] When Pickering hired more women for the project, the group was jokingly called “Pickering’s harem,” but the brilliance of these women couldn’t be denied.[7] Astronomers of international fame came out of the corps of Harvard’s women computers,including Annie Jump Cannon, Henrietta Swan Leavitt, and Cecelia Payne-Gaposchkin.

By 1886 Fleming was placed in charge of the women computers who worked on a project through the Henry Draper Memorial, a research initiative to study stellar spectra, funded by Mary Anna Draper in honor of her deceased husband. Fleming spent the next few years working with Pickering, devising an alphabetic spectral classification system to replace the previous Roman-numeral scheme that had been developed by Angelo Secchi several decades earlier.[8] This scheme was later modified by Annie Jump Cannon and published in the Henry Draper Catalogue of Stellar Spectra in several installments released between 1918 and 1924. Fleming’s additional managerial duties at the Harvard Observatory included the physical care of the photographic glass plates in Harvard’s growing collection, hiring and supervising the work of the other women computers, and preparing the observatory’s publications.[9] She also wrote and published her own paper entitled “A Field for Women’s Work in Astronomy” (1893) in which she explained the research being conducted by other female astronomers at the observatory and made a case for women in her scientific field.

Fleming became the one of the most prominent female astronomers of her time and received numerous awards and honors for her work studying the stars. She was invited to participate in the Congress of Astronomy and Astrophysics at Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893. In 1898, the Harvard Corporation named her the observatory’s first Curator of Astronomical Photographs.[10] In 1906, the British Royal Astronomical Society elected her as an honorary member, making her the first American woman and sixth woman ever to be given this honor.[11] Wellesley College elected her an Honorary Fellow in Astronomy, and she won the gold medal of the Astronomical Society of Mexico posthumously.[12] Throughout her career, Fleming discovered 10 novae, 52 nebulae, and 310 new variable stars.[13] She is also credited with being the first person to see the Horsehead nebula while examining one of Harvard’s glass plate photographs from 1888.[14]

Williamina Patton Fleming died of pneumonia on May 21, 1911.

[1] Lisa Yount, A to Z of Women in Science and Math (New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1999), 65.

[2] Bessie Zaban Jones and Lyle Gifford Boyd, Harvard College Observatory: The First Four Directorships, 1839-1919 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971), 392-3.

[3] Yount, A to Z of Women, 65.

[4] Jones and Boyd, Harvard College Observatory, 392-3; and Alan Hirshfeld, Starlight Detectives: How Astronomers, Inventors, and Eccentrics Discovered the Modern Universe (New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2014), 228.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Yount, A to Z of Women, 65; and Jones and Boyd, Harvard College Observatory, 392-3.

[7] Yount, A to Z of Women, 65.

[8] Hirshfeld, Starlight Detectives, 228; and Jones and Boyd, Harvard College Observatory, 392-3.

[9] Solon Bailey, The History and Work of Harvard Observatory 1839-1927 (New York and London: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1931), 263; and Jones and Boyd, Harvard College Observatory, 392-3.

[10] “Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (1857-1911),” Harvard University Library Open Collections Program: Women Working 1800-1930, accessed February 19, 2015, http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/ww/fleming.html

[11] Yount, A to Z of Women, 66.

[12] Jones and Boyd, The Harvard College Observatory, 394.

[13] “Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (1857-1911).”

[14] Hirshfeld, Starlight Detectives, 143.

Bibliography:

Bailey, Solon. The History and Work of Harvard Observatory 1839-1927. New York and London: McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1931.

Harvard University Library Open Collections Program: Women Working 1800-1930. “Williamina Paton Stevens Fleming (1857-1911).” Accessed February 19, 2015. http://ocp.hul.harvard.edu/ww/fleming.html

Hirshfeld, Alan. Starlight detectives: How Astronomers, Inventors, and Eccentrics Discovered the Modern Universe. New York: Bellevue Literary Press, 2014.

Jones, Bessie Zaban and Lyle Gifford Boyd. The Harvard College Observatory: The First Four Directorships, 1839-1919. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1971.

Young, Monica. “Digitizing Harvard’s Century of Sky.” Sky and Telescope, May 14, 2013. Accessed February 3, 2015.

Yount, Lisa. A to Z of Women in Science and Math. New York: Facts on File, Inc., 1999.

Page citation:

Lindsay Smith. “Williamina Paton Fleming.” Project Continua (March 14, 2015): Vol. 1, (date accessed), http://www.projectcontinua.org/williamina-paton-fleming/

Tags: Astronomers, Industrial Revolution, North America